Does God have More than One Will?

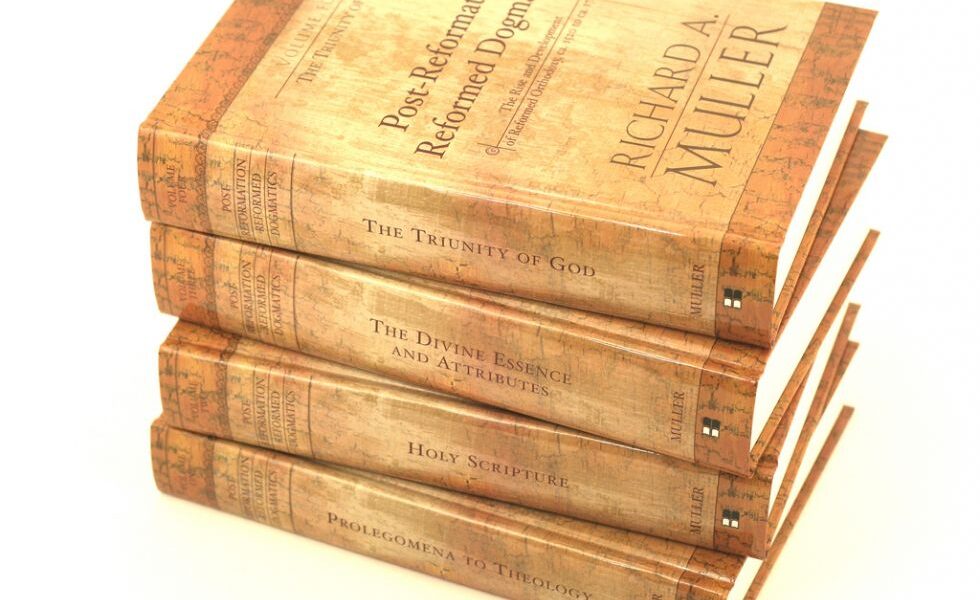

Having looked more closely into the claims of the “eternal submissionists” and those who deny eternal generation, I have to confess that I am more alarmed now than ever at their theological project. As someone with some knowledge of historical theology, much of what I see going on right now can have some much-needed help from the history of Reformed (and earlier) orthodoxy.

To me there are several issues, which I shall draw attention to in order to see how all of theology is related, and when one makes an error in one place there will be ramifications in other places.

1) God’s Will.

Those who hold to eternal submission are decidedly unclear on the nature of God’s will. Many before these men have struggled with the Reformed concept of God’s will. We should be clear on the distinction between God’s “natural will” that relates to internal (ad intra) Trinitarian relations and God’s “free will” that relates to God’s ad extra works. Karl Barth was unclear on this distinction (see E.P. Meijering, Von den Kirchenvatern zu Karl Barth, 66-67).

There appears to me to be no real awareness of distinctions of the essential and accidental, necessary and contingent, ad intra and ad extra dimensions of God. From what I can tell so far, it seems to me that “eternal submissionists” are having to deny that God has one (ad intra) necessary will. Michael Ovey’s recent defense of himself only made matters worse, in my view. His piece leads me to the conclusion that he has to give up an orthodox understanding of God’s will, even if he doesn’t have to give up his job.

As I understand Reformed orthodoxy, we can speak of the triune God’s ad intra will in the following manner:

1. God’s will in relation to his independence: he wills of himself and is not induced by others to will whatever he wills.

2. God’s will consists of one, indivisible act: because of God’s simplicity and his will being identical with his essence, there cannot be different acts of willing in God. (On this view, eternal submission makes no sense whatsoever).

For these reasons, and others, I have to sympathize with my brothers who are raising concerns about “tritheism.” That God has one will leads to a host of other important ramifications for our theology. Because God has one will, but this one God is three persons, we affirm that the external works of the Trinity are undivided:Opera Trinitatis ad extra sunt indivisa. Hence Thomas Goodwin will argue: “It is a certain Rule, that Opera Trinitatis ad extra sunt indivisa, all their works to us-ward of Creation and Redemption, and whatsoever else, they are all works of each Person concurring to them. As they have but one Being, one Essence, so they have but one work.”

However, because they have several subsistences (modus subsistendi), the persons each do different works (e.g., the Son dies, not the Father). Notwithstanding this basic principle of attributing ad extra works to all the persons of the Trinity, we can argue that certain outward works – depending on what they are – are more peculiarly attributed to one of the persons. That is to suggest that the persons all share a common prerogative, but often a certain work will be attributed to the Father, for example, in order to display his uniqueness. Reformed theologians have claimed that the undivided works ad extra often manifest one of the persons as their terminus operationis.

For example, the incarnation terminates on the Son though the act is willed by the three persons of the Trinity. This is what Michael Ovey has so much trouble with when he speaks of Christ doing the will of the Father. He cannot possibly see how the will of the Father includes the Son and Spirit. He ends up confusing agency and personality with will, which is an old error. But, since God’s outward will is one (as his inward will is), the will of the Father is also the will of the Son and the Spirit. But ad extra works often manifest one of the persons as their terminus operationis, as I say above. Ovey basically has to end up denying that Christ has two wills, which would lead him into the error of monothelitism.

Now, if the “eternal submissionists” were only saying that Christ, as God-man, submits to the Father there would be no debate. As an ad extra reality, we all affirm this. But they are doing something very different, namely: they are affirming there is an eternal ad intra submission of the Son to the Father. This, to me, necessarily disrupts divine unity and leads to a rejection of the orthodox understanding of God’s will. Eternal submission necessarily posits two wills in God. Simplicity goes out of the window; and, furthermore, the oneness of God (una essentia) is compromised.

Suggesting submission in the Godhead jeopardizes not only our doctrine of God, but also our doctrine of Christ.

Click to Tweet

Both of those, historically considered, would be deemed heretical.

If you think these are small issues that are not worth fighting over, they are not. Consider the 2nd Helvetic Confession (ch. 3):

HERESIES. Therefore we condemn the Jews and Mohammedans, and all those who blaspheme that sacred and adorable Trinity. We also condemn all heresies and heretics who teach that the Son and Holy Spirit are God in name only, and also that there is something created and subservient, or subordinate to another in the Trinity, and that there is something unequal in it, a greater or a less, something corporeal or corporeally conceived, something different with respect to character or will, something mixed or solitary, as if the Son and Holy Spirit were the affections and properties of one God the Father, as the Monarchians, Novatians, Praxeas, Patripassians, Sabellius, Paul of Samosata, Aetius, Macedonius, Anthropomorphites, Arius, and such like, have thought.

2) Christ’s Wills

To Come

3) Biblicism & Lessons from History

To Come